All images courtesy of Andreia Alves De Oliveira

The Borough at War: LSBU and Southwark, 1914-1918 /

An exhibition to mark the centenary of the Armistice, looking at the First World War through the records of LSBU and Southwark Local History Library & Archives. The exhibition includes First World War art work by David Bomberg, as well as archives from LSBU and Southwark which tell the story of the First World War through the records of students, staff and local people. Find out about how the Borough Polytechnic contributed to the war effort at home, as well as stories from those who went to fight on the Western Front and beyond. Find out more here.

War bonds demonstration c 1918 courtesy of the Southwark Archives

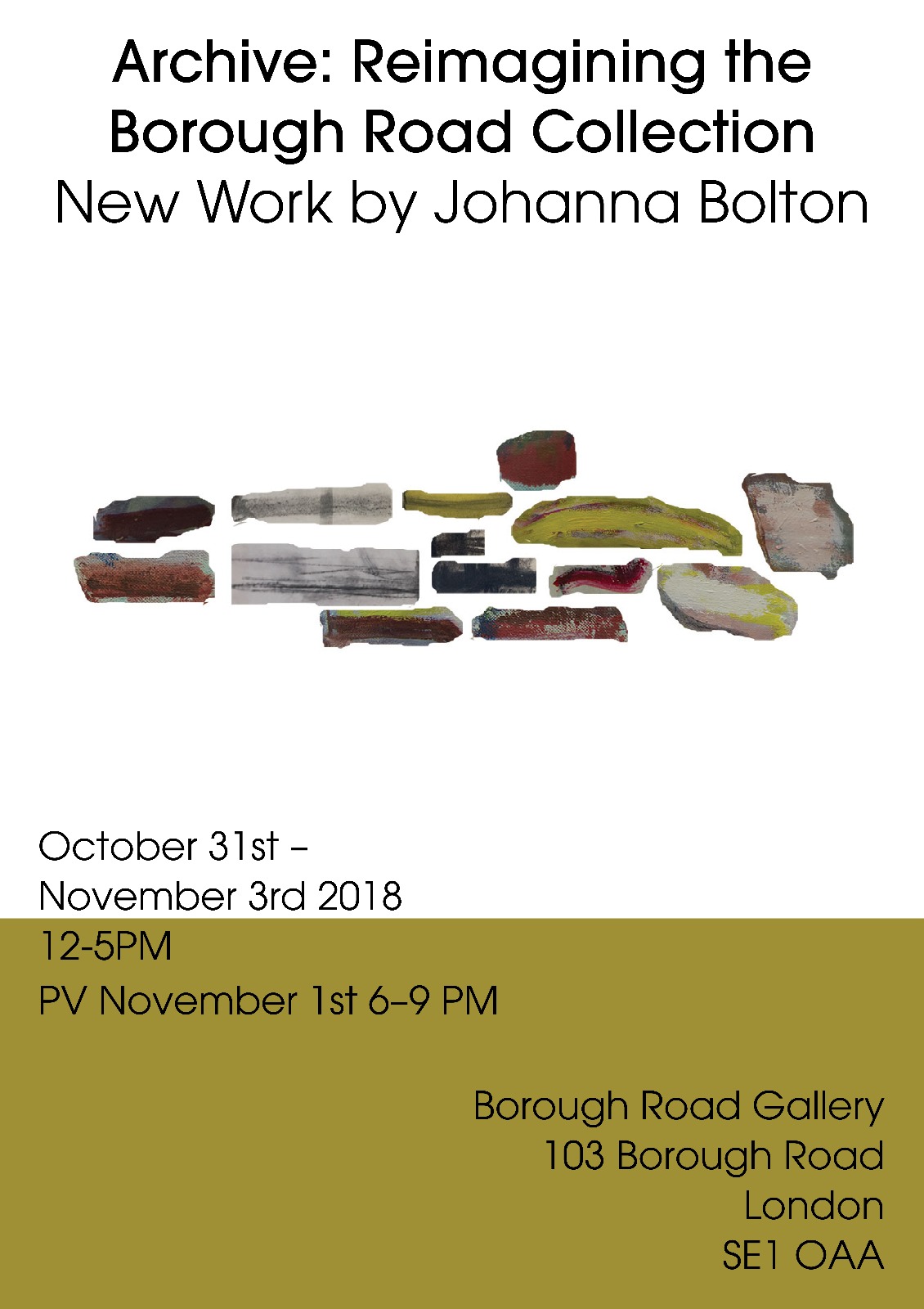

Archive: Re-Imagining the Borough Road Collection /

Poster by Christian Corless

Southwark Local History Library and Archive /

This week we are featuring selected images and archival documents that highlight the history of Elephant & Castle at a time when Bomberg and the Borough Group were working in the area taken from the Southwark Local History Library and Archive. To see the full set of images follow us on Instagram or Twitter.

If you would like to learn more about their collection please contact them at: local.history.library@southwark.gov.uk.

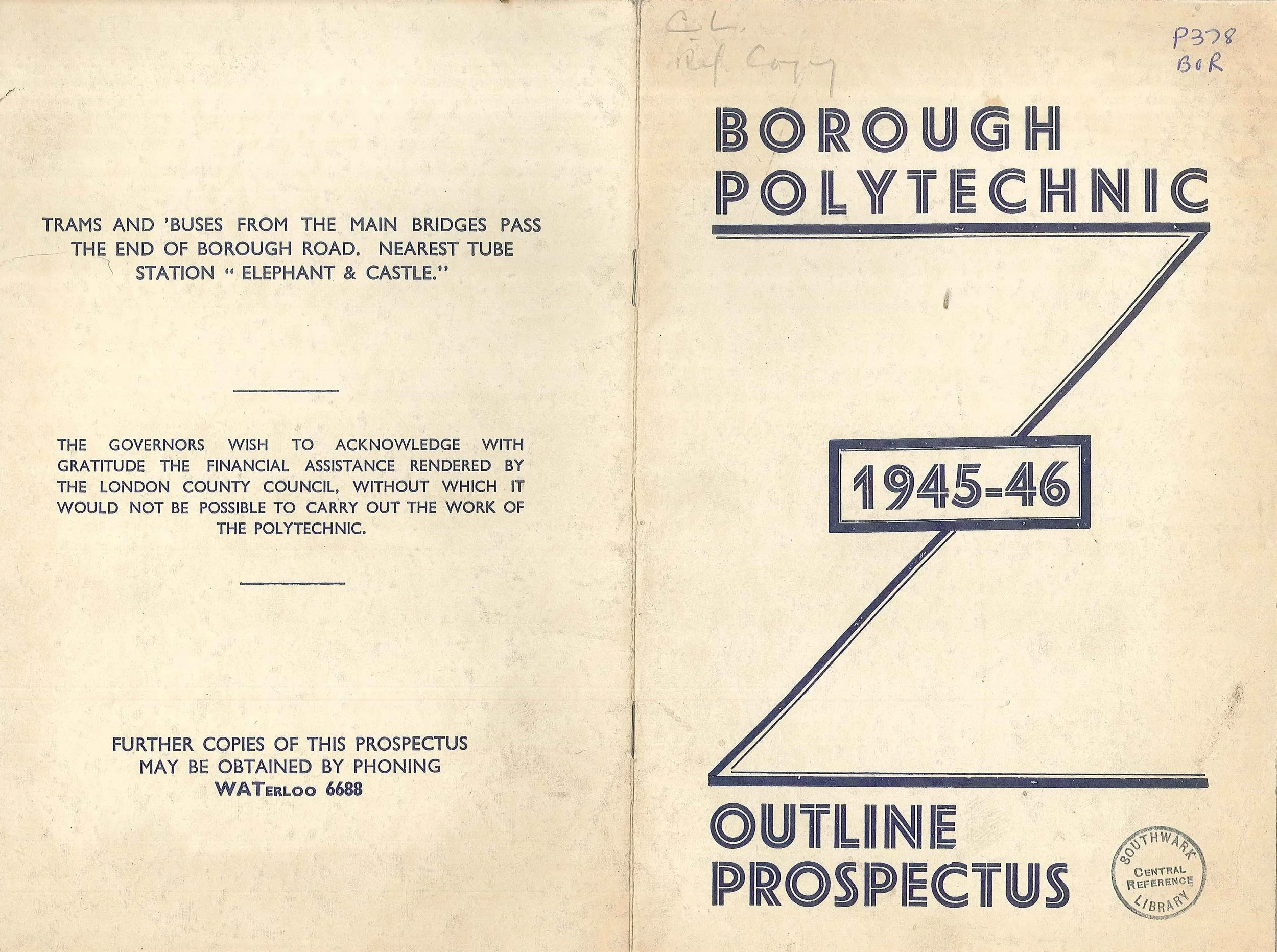

Borough Polytechnic Prospectus 1945 – 1946.

The outline prospectus for the Borough Polytechnic in David Bomberg’s first year in teaching.

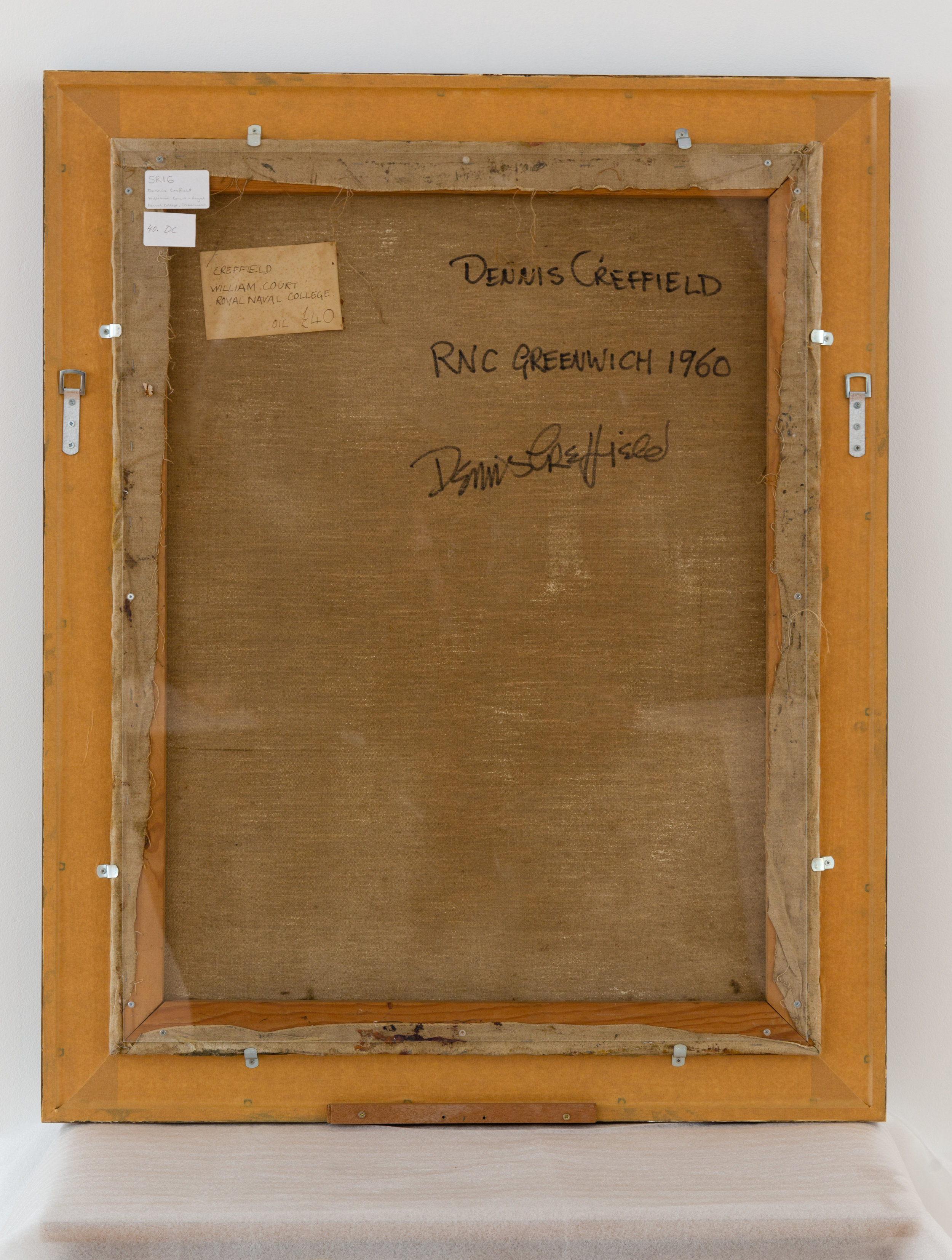

Behind the Painting /

The frames and mounts of paintings are themselves unique canvases of hidden detail. Our tendency to overlook the effects of framing discounts their having existed for as long as pictures have been mobile. The French post-structuralist Louis Marin described the picture frame as a device which “renders the work autonomous in visible space”, putting “representation into a state of exclusive presence.” When framed, the painted picture becomes a worthy object of contemplation and demands absolute attention. Simultaneously, the frame effaces itself, becoming obsolete in the eyes of the viewer, entirely separate from the work of art it borders.

While frames have historically been designed by artists to accentuate their pictures or chosen by patrons and museums in line with current fashions, frames are primarily physical supports which protect paintings against their surroundings. The frame’s role is one of mediation. Paintings derive the visual autonomy identified by Marin from the exclusive physical and symbolical safety the frame provides, a condition which relates back to what Walter Benjamin had previously characterised in 1936 as the ‘aura’ of the work of art.

Rooted in an object’s authentic presence in time and space, and the physical changes it has undergone since its creation, the ‘aura’ is perhaps most legible in the frame of a painting which has both facilitated and borne witness to the work’s movements between people and institutions. For Benjamin, the irreproducibility of these conditions reveals the power of a work of art as historical testament.

By documenting the backs of paintings and drawings, this series brings the Borough Road Collection Archive into focus as being comprised of mobile and changeable three-dimensional objects that have each passed through different hands to arrive in the current collection. The diverse materials used by the artists themselves, the size and style of frames, and the presence of various labels and notations identifying craftsmen and galleries together constitute individual time capsules to be unpacked and interpreted. Utilising reproductive technology in this post-internet context serves to re-articulate rather than wither the ‘aura’ of the artworks in the collection, exhibiting a side to them rarely seen by the public.

Excavation: Scott McCracken's Paintings. By Phil King. /

In the early 1920s, animation promised to annihilate painting, or to show it up for what it had become – static, ever same, trapped within the confines of a frame that had become a kind of prison, cut off from the world and from life, or from the lively principle that suffuses all life worth living. Animation promised – for the critic and filmmaker Hans Richter – twenty-four Mondrians a second, which is so much better than one. Animation pledged kaleidoscopic experience. It promised not only to exceed painting through mobility and rhythm but also to do what cinema should do and was failing to do, as it became a conventionalised form, a banal representation.

From: Interview with Esther Leslie: For A Marxist Poetics of Science

Borough Art Labs /

This summer’s programme at The Borough Road Gallery comprises a set of quickfire events showcasing a range of local artists and performers. ‘Borough Art Labs’ takes its name from the original ‘Arts Lab’ which opened on Drury Lane in 1967, and that functioned as a space for the fusion of fine art, theatre and cinema, detached from the agendas of mainstream arts institutions. The success of this London space catalysed the establishment of other independent centres around the world, dedicated to the collaborative propagation of alternative arts.

Read MoreDavid Bomberg’s niece, Cecily Bomberg in conversation with Nicola Baird, PhD candidate, /

David Bomberg’s niece, Cecily Bomberg in conversation with Nicola Baird, PhD candidate, LSBU:

NB: I wondered if you could explain how you relate to David Bomberg?

CB: My father, John was the baby of the Bomberg family, my mother, Olive was 12 years his junior, an Irish Catholic girl. David was my uncle and he was very keen on my mother because she turned my father around and put him on the straight and narrow- he adored her. David had been 22 when his mother died, he was already launched and she’d done everything for him but my father was 7 so you can imagine and then the others were all older and grown up so you can imagine what he went through….

NB: What are your memories of David Bomberg?

CB: What are my memories? His personality and little things about him are really what I know, mostly of course because I was only 15 when I last saw him, that’s how old I was and so mostly of course it is childhood memories. My first memory of him was in a camp in Wales at the end of the war, we were sent there, I think, because of some very late bombing. My mother had us in a hotel and every day we’d go into the fields to visit my uncle and aunty Lilian and Diana who were staying in a tent there, I remember I hated going there because he might have been a bit moody, I don’t know. She loved animals, but he hated them, he thought they should all be of purpose, I had a pet dog, my first dog, Nuala and what he did was he took her into the sea with him to bathe, cleanliness was a big thing with him, he used to even wash his suits in the sea, he took her into the sea and she was the soap holder, he put carbolic soap in her mouth! I remember him in the camp there, I’ve always had a word difficulty, I was a little dyslexic, and he obviously was in a mood but he liked joking, so one day he said to me, I was about 5, go into the farm and get the letters, and of course I brought him back a head of lettuce, so every time I would go there to visit he said where’s Cecily, Cecily I need my letters, and I would come back with the head of lettuce and they would all laugh at me. The next really strong memory I have of him is that whenever he came to visit us and my parents would ask, Cecily, do you want to ask Uncle David something? And then I had something that I had wanted to ask someone, you know anyone, and they would say ask Uncle David like he was the great sayer, is that how you say it? It’s like he was the oracle or something, now that is my real strong memory of him, and I would have been about 8 or 9 maybe. To me he spoke like a foreigner, he spoke slowly and methodically and every word was weighed, he would be thinking and carefully weighing but by the time he had finished I couldn’t remember what I’d asked! He liked me as a child because I was quiet, I wasn’t a running around child and he thought, that I should be put to music, there was something sad about me and that I needed solace and that the violin would be a good thing for me. Somebody told me that he actually purchased the violin, but I don’t think he ever had that much money. I wish I had known him as an adult, I wish I had been old enough to respond as a young woman as my mother had to him, to really learn from him and to see what a fine person he was, but I’m afraid I was just a little child and I thought of him as a vagabond of sorts coming and going, sometimes he wore a dressing gown at least I can remember him in a dressing gown and bandana, I think I saw him out once in a dressing gown.

NB: Which are your favourite works by David Bomberg?

CB: I think some of the portraits are marvellous; yes I like them a lot. For some reason I love the Cyprus paintings, they do something to me, of course the Spanish paintings, how could I not? And I do love some of the Palestinian paintings, the Church of the Armenians, the beautiful blue church in Jerusalem- some beautiful works. I love the Petra and I think the Cornish, that lovely painting of Cornwall and Devon, I see them all as I’m saying them now there’s so many, I think I prefer them all to the ones my family had. I wish he had done more portraits, the one that you and I met in front of, I really thought a lot of that portrait, and then there’s this other one, of a man who’s a great friend of his, I think that’s in the Ben Uri Gallery collection [John Rodker] , Jimmy Rodker, what David used to call, ‘my blood brother’, this is all my mother telling me, they were great friends and I love that picture….but I do wish he had done more portraits, I love Kitty’s portrait. I love the Ghetto Theatre and things like that, I’ve been very impressed with the Ben Uri, very impressed with what I’ve seen there, some beautiful paintings, and one of them which strikes me as quite strange is the racing picture, the race, that was an extraordinary picture, that was done in about 1912 I think, and just to see the composition, I mean, when you keep looking at it, it does something to you, I very much go in for the Ghetto and all of his pictures.